So far, evidence suggests that the number of Covid-19 cases and deaths in Australia has been lower than in many other countries , even if the outbreak can’t be considered to be under control just yet.

Australian hospitals also appear to have coped relatively well with the influx of Covid-19 patients and one potential reason for this is that there was a reasonable amount of additional capacity to start with. Of course, actions taken by the Government and individual states and hospitals have had an impact too, including the cancellation of elective surgery and the use of flexible modular infrastructure that can be made operational very quickly.

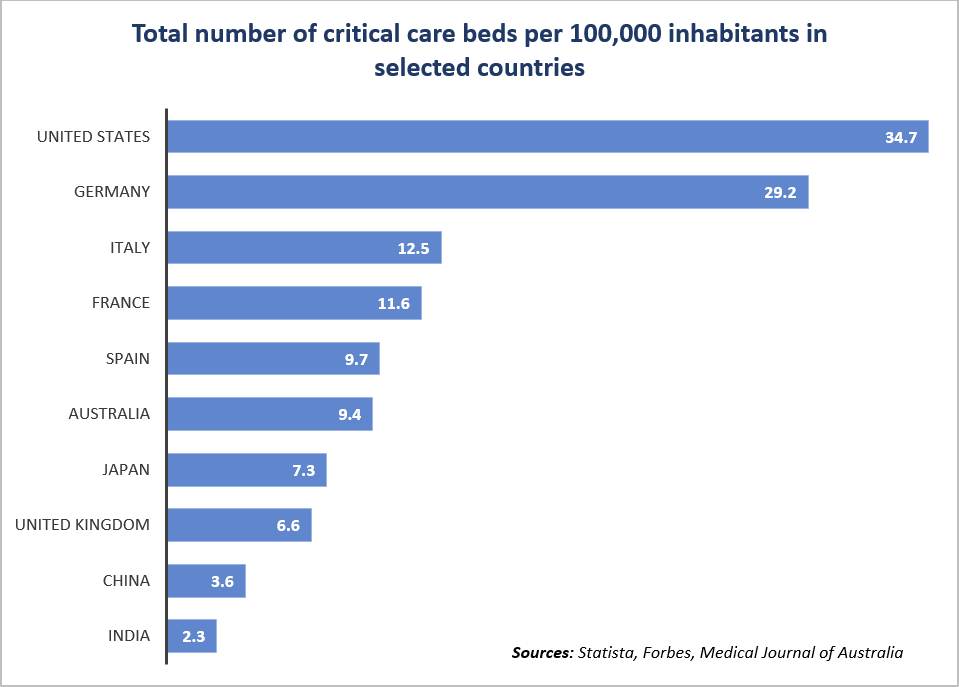

While it is too early to speculate around the outcome, it is interesting to look at how Australia’s ICU capacity compares with that of other countries. Official figures show that there are 191 intensive care units in Australia, with a total of 2,378 available intensive care beds during baseline activity – representing roughly 9.4 ICU beds per 100,000 population. The figures were collated before the crisis and therefore do not include any beds added in hospitals or temporary wards or so called ‘field hospitals’ since.

An

international comparison

indicates that Australia has more intensive care beds per population than many countries including the United Kingdom, which has roughly 6.6 beds per 100,000 people, Japan (7.3) and China (3.6), but significantly fewer than the United States (34.7) and some other major European countries. The number is also slightly lower than in Canada, which is relatively close in terms of population size and is estimated to have between 10-12 ICU beds per 100,000 inhabitants depending on the method used for the calculations.

In addition, a

recent modelling exercise

on the surge capacity of Australian intensive care units, which was published at the end of March in the

Medical Journal of Australia

, found there was potential to nearly triple intensive care bed capacity in response to predicted increased Covid-19 demand.

In addition, a

recent modelling exercise

on the surge capacity of Australian intensive care units, which was published at the end of March in the

Medical Journal of Australia

, found there was potential to nearly triple intensive care bed capacity in response to predicted increased Covid-19 demand.

According to the study, Australian ICUs could surge the number of ICU beds by an additional 4,261 (189%) if needed. At that level, however, there would be a shortage of ventilators and likely also PPE equipment. The study estimated that the surge potential of ventilators is just over 2,000, so would only partly meet the maximum surge capacity in terms of beds.

Another issue potentially restricting capacity would be the healthcare workforce needed to operate the ventilators. The modelling exercise showed that at maximum surge capacity, up to an additional 4,000 senior doctors and 42,700 registered ICU nurses could be required.

To date, there is still spare capacity in most Australian hospitals, while many countries in Europe with higher numbers of Covid-19 cases, such as Italy, have been under more pressure. Time will tell if this situation will last, given that the winter season is approaching, and a second wave of cases is possible.

Making fair international comparisons is difficult as countries have different healthcare systems and different ways of collecting statistics, and it should be noted the reliability in the ICU bed numbers reported varies between countries, as does the age of the data and the methods used for calculations. Nevertheless, the figures provide a basis for general comparison.

Once the pandemic is over, or we’re at least seeing a return to some levels of normality, it will be interesting to see what effect the current crisis will have longer term on the number of ICU beds worldwide. It is possible that the baseline ICU capacity will change permanently in some countries as a result of the additional beds that have needed to be created as a result of the Covid-19 outbreak, while the high number of additional ventilators that have been manufactured to deal with shortages could also have a positive impact.

Q-bital Healthcare Solutions

Unit 1144 Regent Court, The Square, Gloucester Business Park, Gloucester, GL3 4AD